Gian Piero Gasperini’s AS Roma Tactical Analysis 25-26

In this article, the tactics of AS Roma under Gian Piero Gasperini are going to be analysed in detail.

After leading Atalanta to the champions of Europa League by beating Leverkusen who had been unbeaten until the final two seasons ago, Gasperini moved to the capital of Italy. His signature style of play is being implemented at his new club and at the same time, he also manages to stay in the top four in Serie A.

His characteristic style of play both in and out of possession is going to be analysed in detail and I hope you enjoy this article.

In Possession

In possession, Gasperini instructed the midfielders to drop deep or drift outside to create overloads outside of the opposition defensive block. This enables them to exploit the overloads on the flanks or play through the middle where they intentionally open up.

Firstly, how they build up from the back is going to be discussed.

Build up

They don’t stick to play out from the back against extreme high pressing, but when playing short from the goalkeeper, they mainly build up from the back with purpose.

One of their characteristics of Roma is that they prefer to play in wide areas. Many possession based teams don’t like to play outside because the opposition can lock them in there, so the pressures are likely to be high and the space is limited.

However, Roma are doing the opposite. They are willing to play to the wide centre backs who are close to the touchlines. In wide areas, they will be locked in easily and pressed man-to-man, so to beat this, Roma try to make dynamic movements.

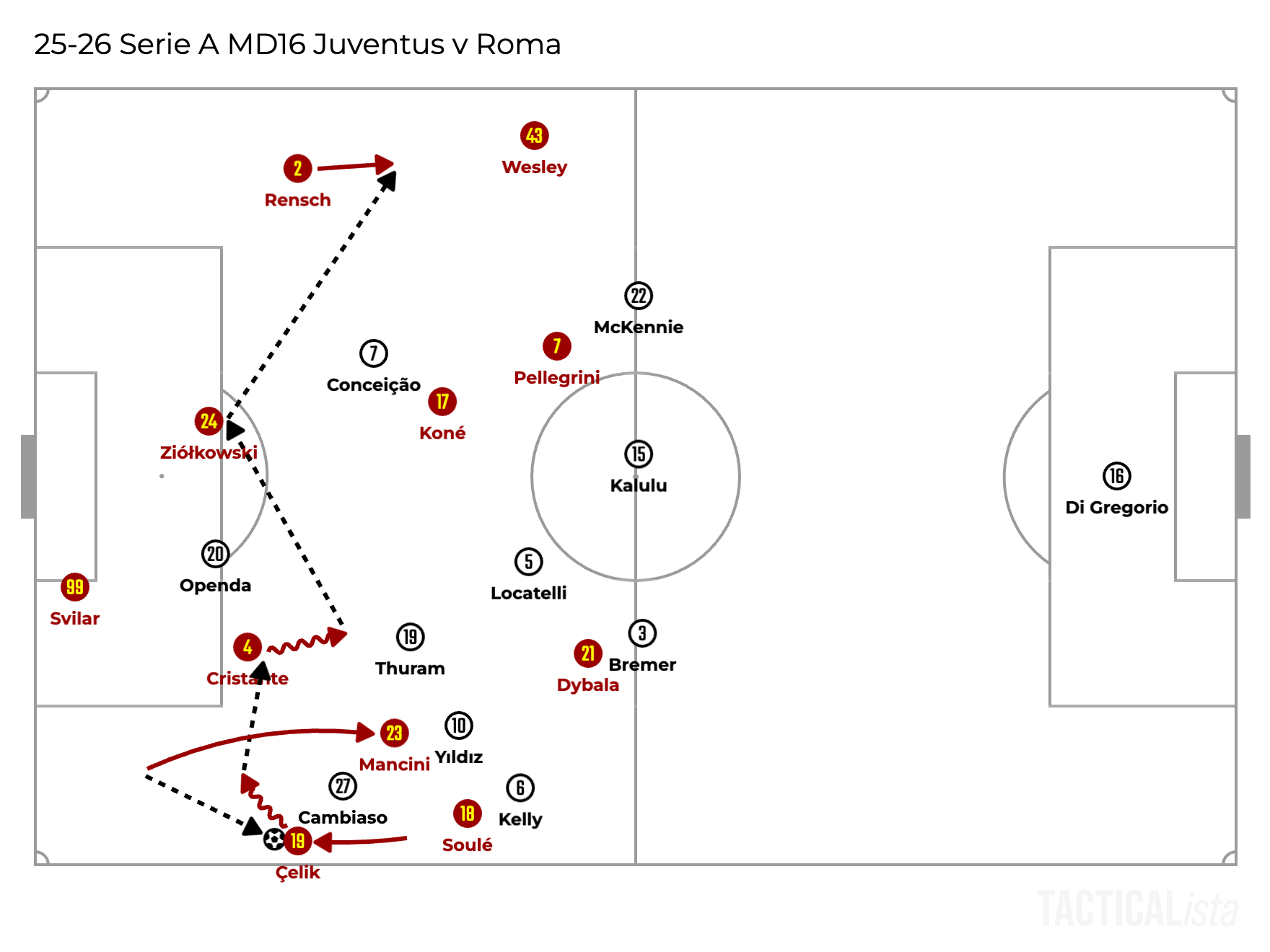

The illustration below shows how they played away from Juventus’ pressure and switched the ball to the left side to progress into the opposition half.

Not only limited to the phase of building up, the wide centre backs don’t hesitate to leave their positions and step forward after passing the ball to the wingbacks.

In the illustration above, Gianluca Mancini played to Zeki Çelik and moved higher with dragging the opposition winger Kenan Yıldız to vacate space at the back. Then, Çelik drove backwards away from his marker behind him to create time and found the defensive midfielder Bryan Cristante who eventually switched the ball to the opposite side.

This was one of the ideal ways of playing away from the opposition pressure. However, when the opposition press man-to-man, there are 1v1s against the opposition defenders up front, so exploiting the space left behind the opposition back line is also likely to be effective.

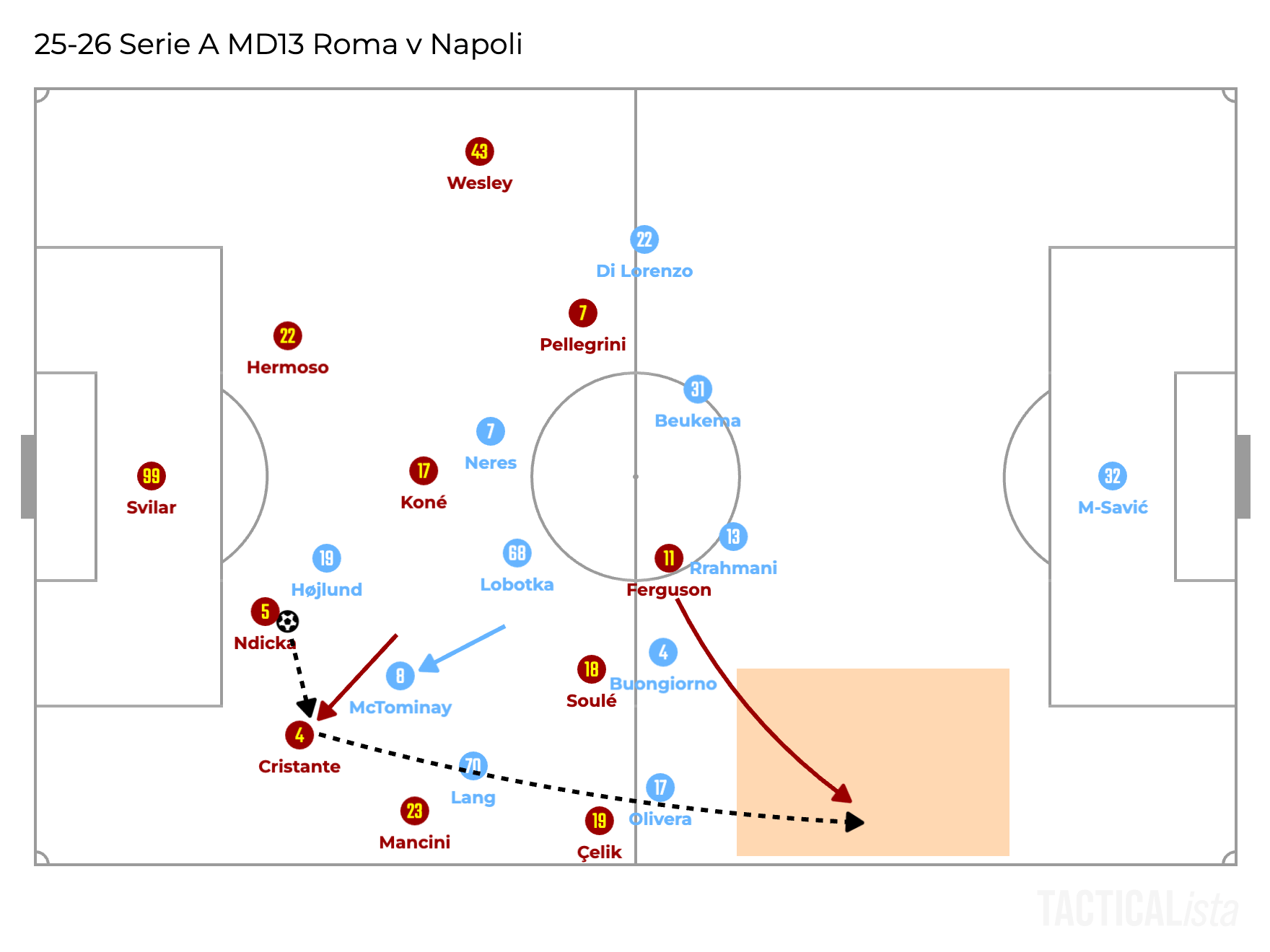

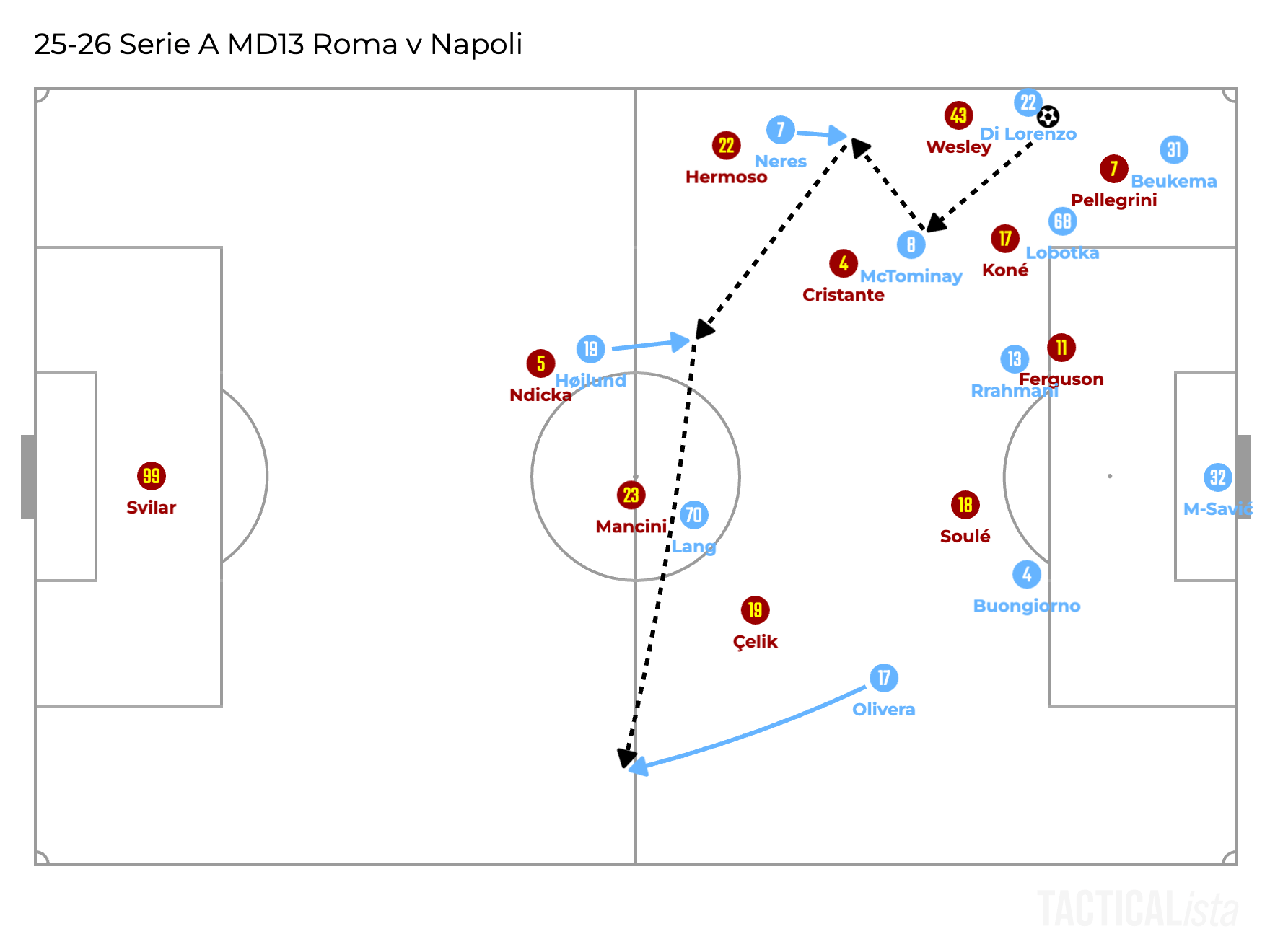

One of the examples of playing directly in behind against Napoli is illustrated below.

As it is shown by an arrow, the defensive midfielder Cristante dropped in between the central centre back Evan Ndicka and the right centre back Mancini. This movement is often performed by both defensive midfielders to let them receive the ball with facing forward and easily find the options up front.

In this scenario, the opposition defenders were marking each Roma’s attacker in the ball side and they were focusing on getting close to each marker and not ready for a long ball in behind well. Then, the striker Evan Ferguson found the gap in the wide area and made a diagonal run into the space, and Cristante tried to meet him with a simple long ball.

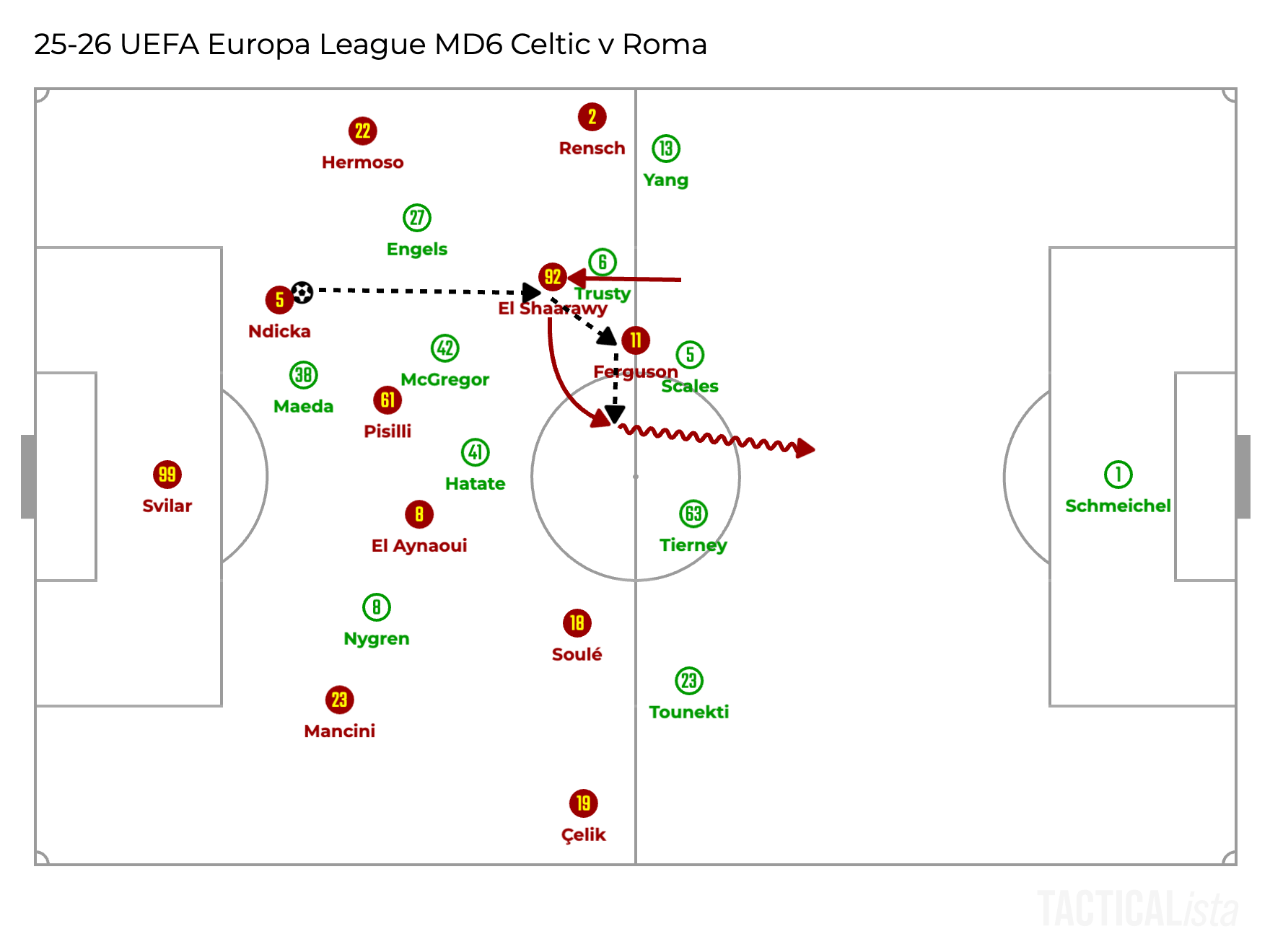

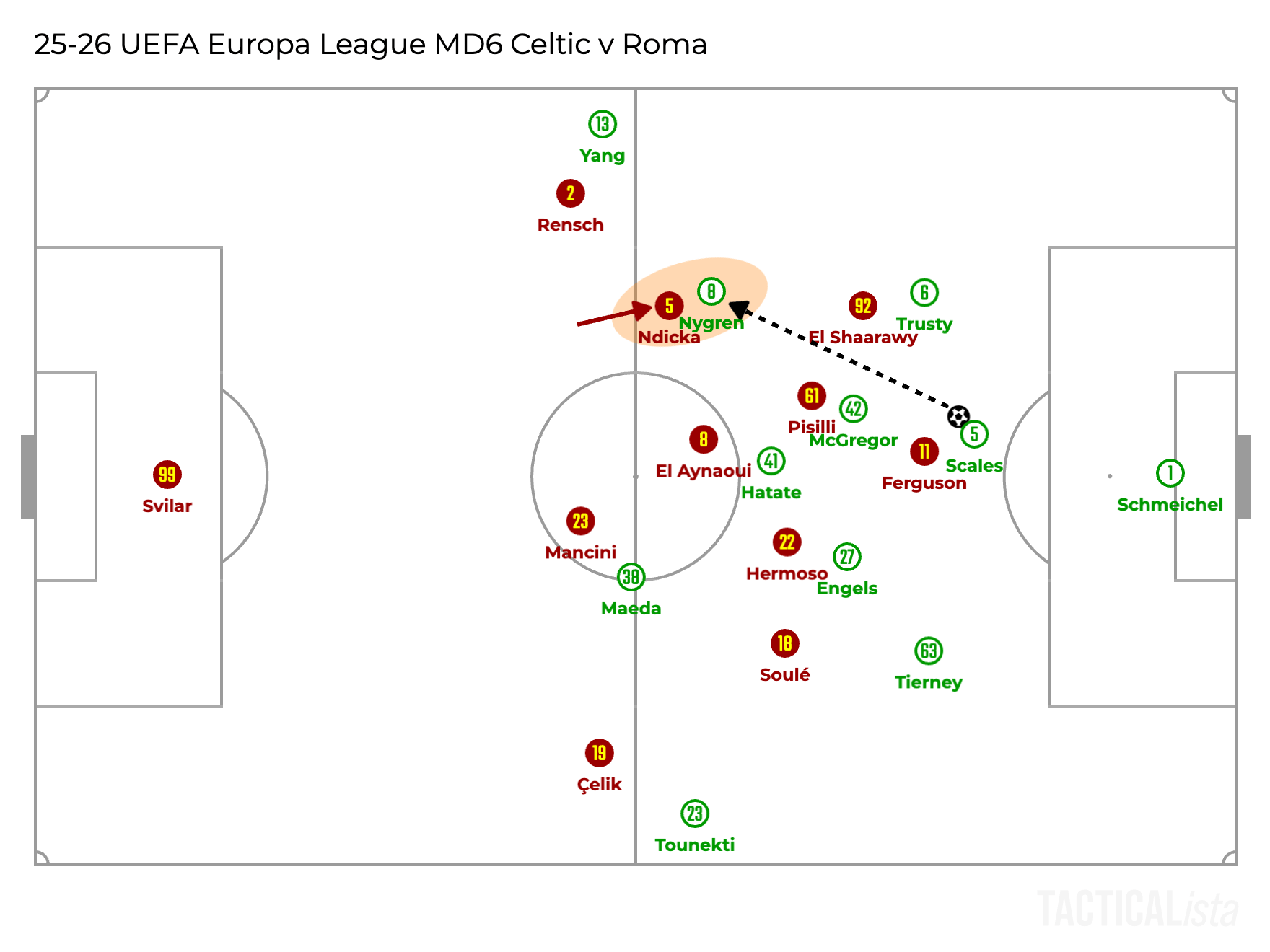

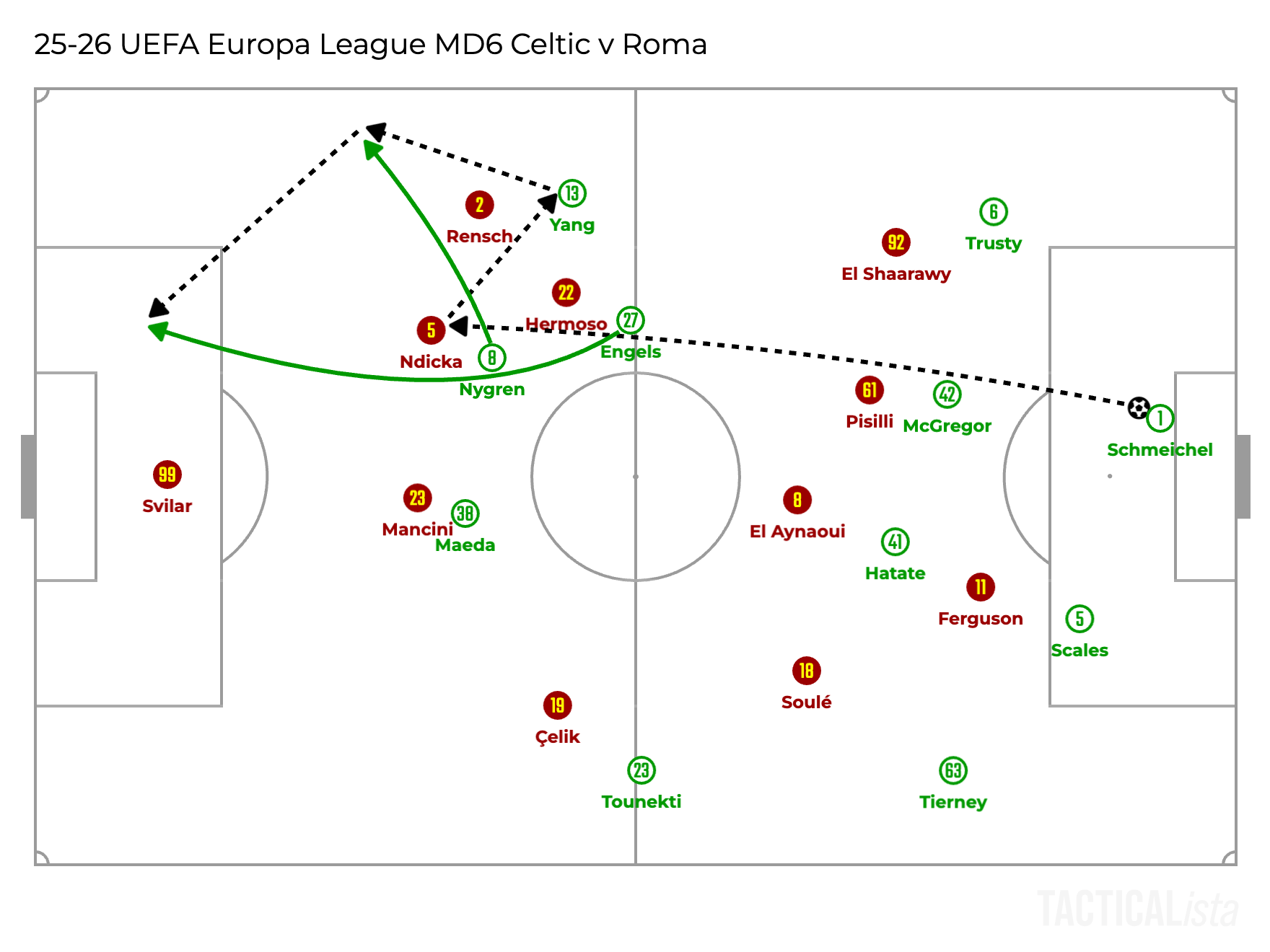

Another example of exploiting the 1v1s up front was seen against Celtic in the Europa League as well.

There were huge differences in individual qualities in this game though, the left attacking midfielder Stephan El Shaarawy dropped to receive a split pass from Ndicka with his marker behind him. After receiving it, he linked up with Ferguson and they successfully beat this 2v2 around the centre circle and went straight to the opposition box.

In the phase of playing out from the back, Roma are very orthodox. They are willing to play safe, can switch the ball and play direct quickly. In terms of the characteristic of their positional approach, as it was mentioned just before, the movement of the defensive midfielders dropping into the back line is fundamental to their game and will be analysed more in detail in the next chapter.

Possession in the Middle

By dropping the defensive midfielders into the back line, they can create a hub for progression. As they can possess the ball in an open body shape in front of the opposition defensive block, it becomes easier for them to find better options to break the lines.

Another advantage is that by tweaking the shape, the defensive midfielders can receive the ball outside the opposition front line, so this also helps them to find the options in between the lines easier.

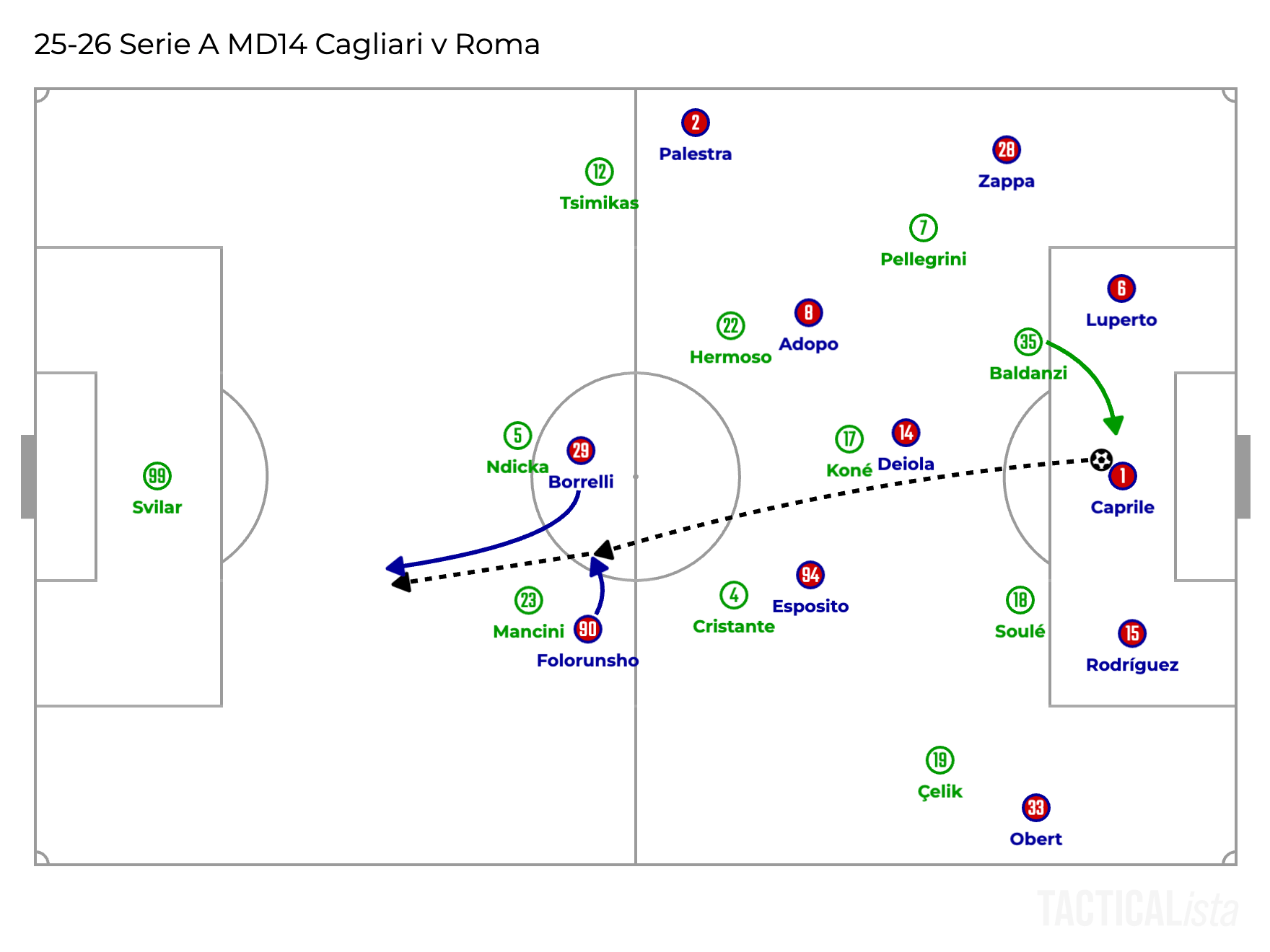

The illustration below shows how they played through the opposition midfield line against Cagliari.

Cristante dropped in between Ndicka and Mancini and received the pass from Ndicka beside the opposition front two. As both of the opposition front two were closing the middle well, Cristante’s movement to leave his position in the middle and receive the ball away from them was clever and designed as a team.

Another example of creating dislocations by the defensive midfielders dropping deep is illustrated below.

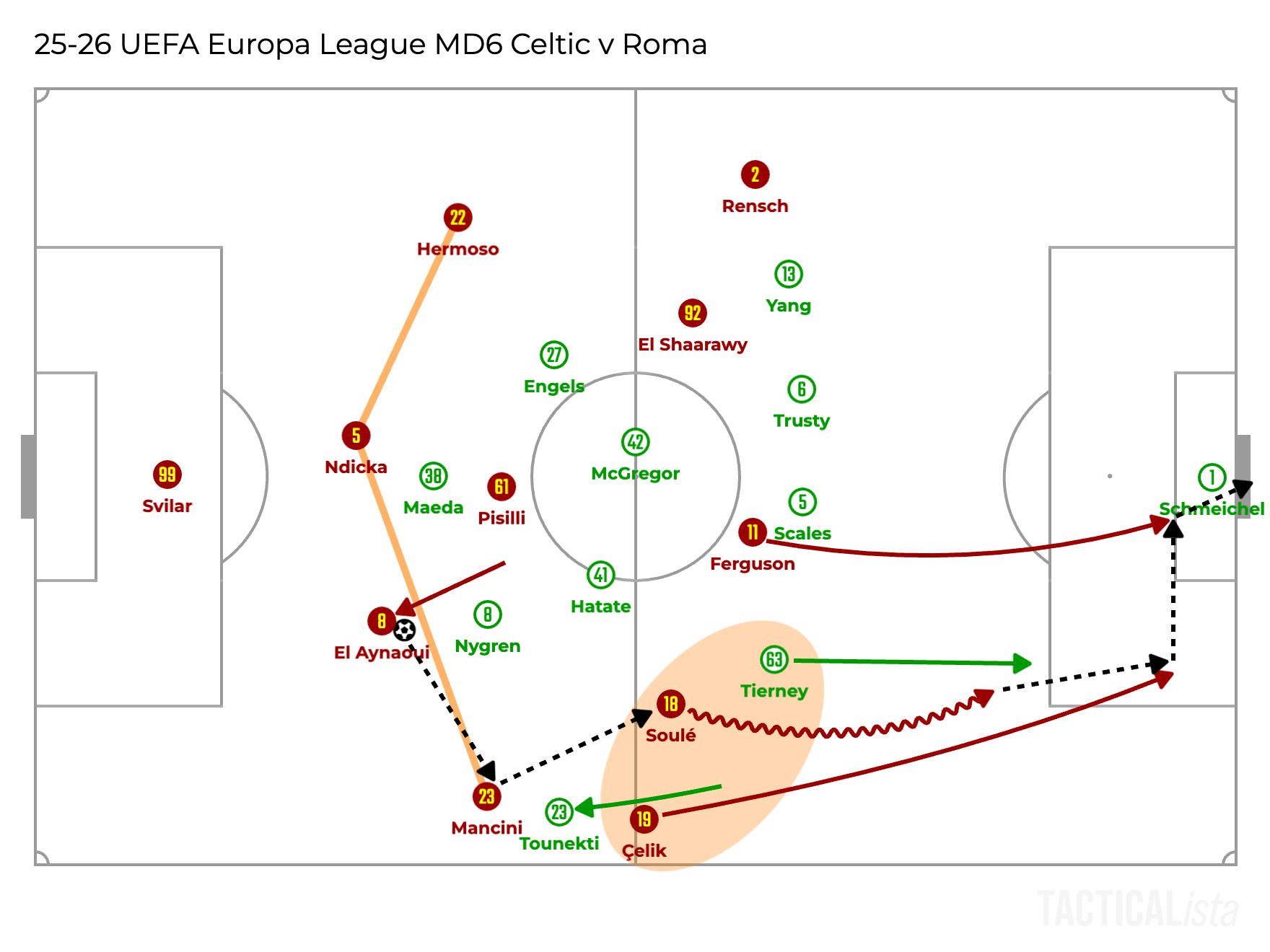

Against Celtic, Neil El Aynaoui dropped into the back line and this caused the misalignments. In this game, Celtic tried to match up Roma’s shape as both played in the 3-4-3, but this movement disrupted their plan.

If El Aynaoui stayed in his usual position in the middle, the opposition left winger Benjamin Nygren would have easily closed down Mancini as he got the ball. However, as El Aynaoui dropped in between the two centre backs, Nygren switched to apply pressure on him instead of Mancini. Therefore, when Mancini received the pass from El Aynaoui, the wingback Sebastian Tounekti was forced to leave his position to close Mancini down, vacating the space behind him to exploit. At the end, Ferguson scored the second for Roma.

This sort of combination in wide areas is one of Roma’s or Gasperini’s strengths, and will be the main topic in the next chapter.

Final Third Attacking

Playing in wide areas is fundamental to Gasperini’s game model.

When building up, the defensive midfielders often drop into the back line, so the wide centre backs are able to stay wide and step up forward. In addition to this, from the midfield to the attacking third, the attacking midfielders also drift outside to create overloads in wide areas.

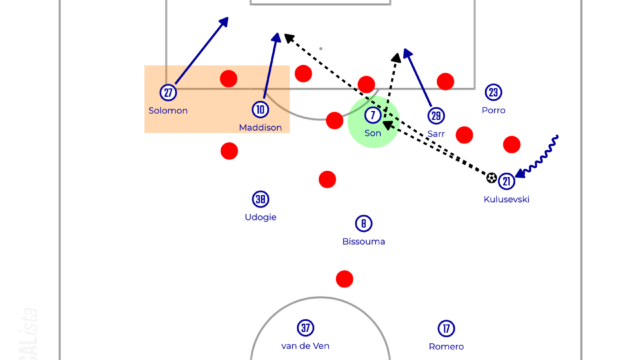

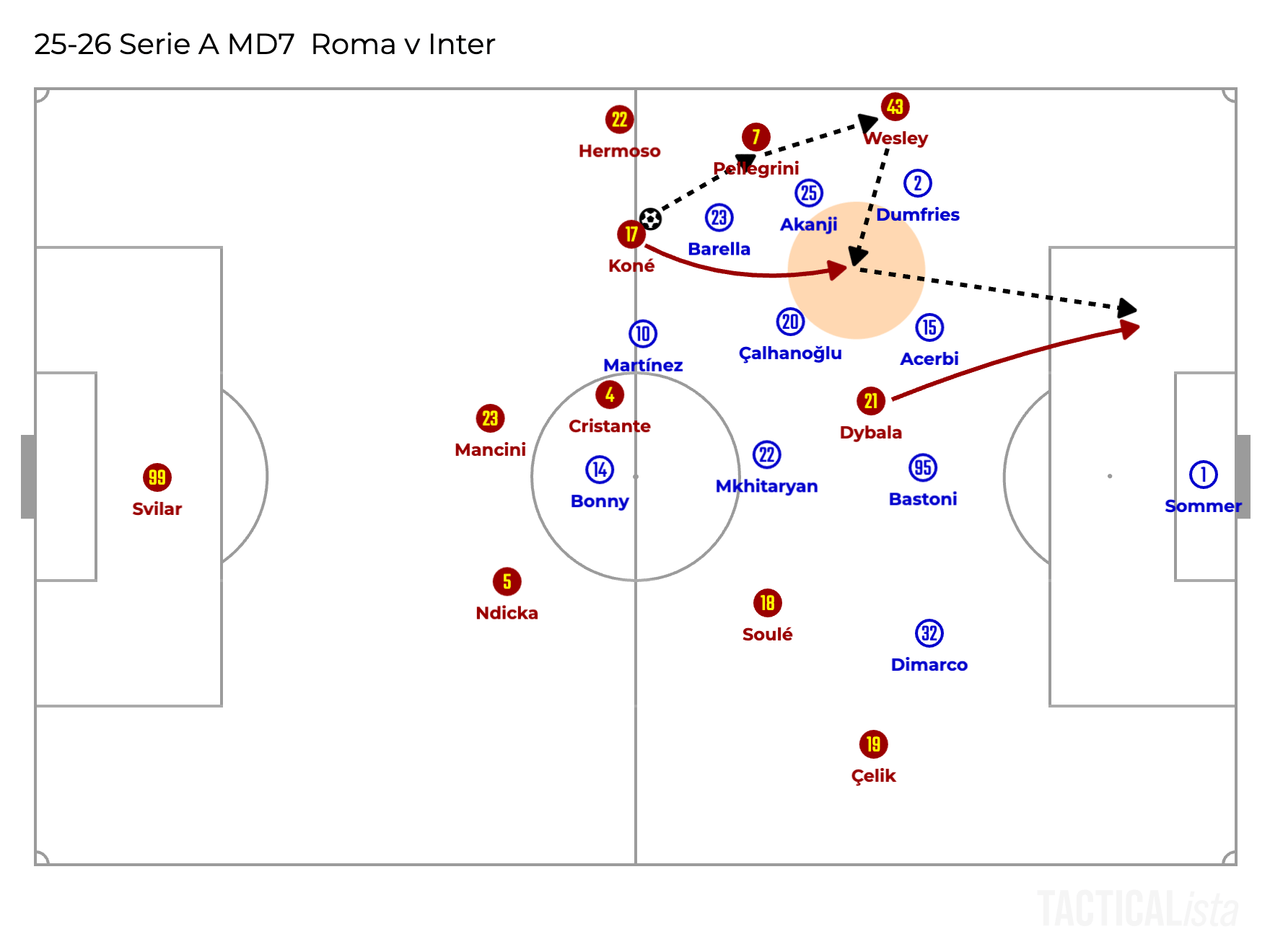

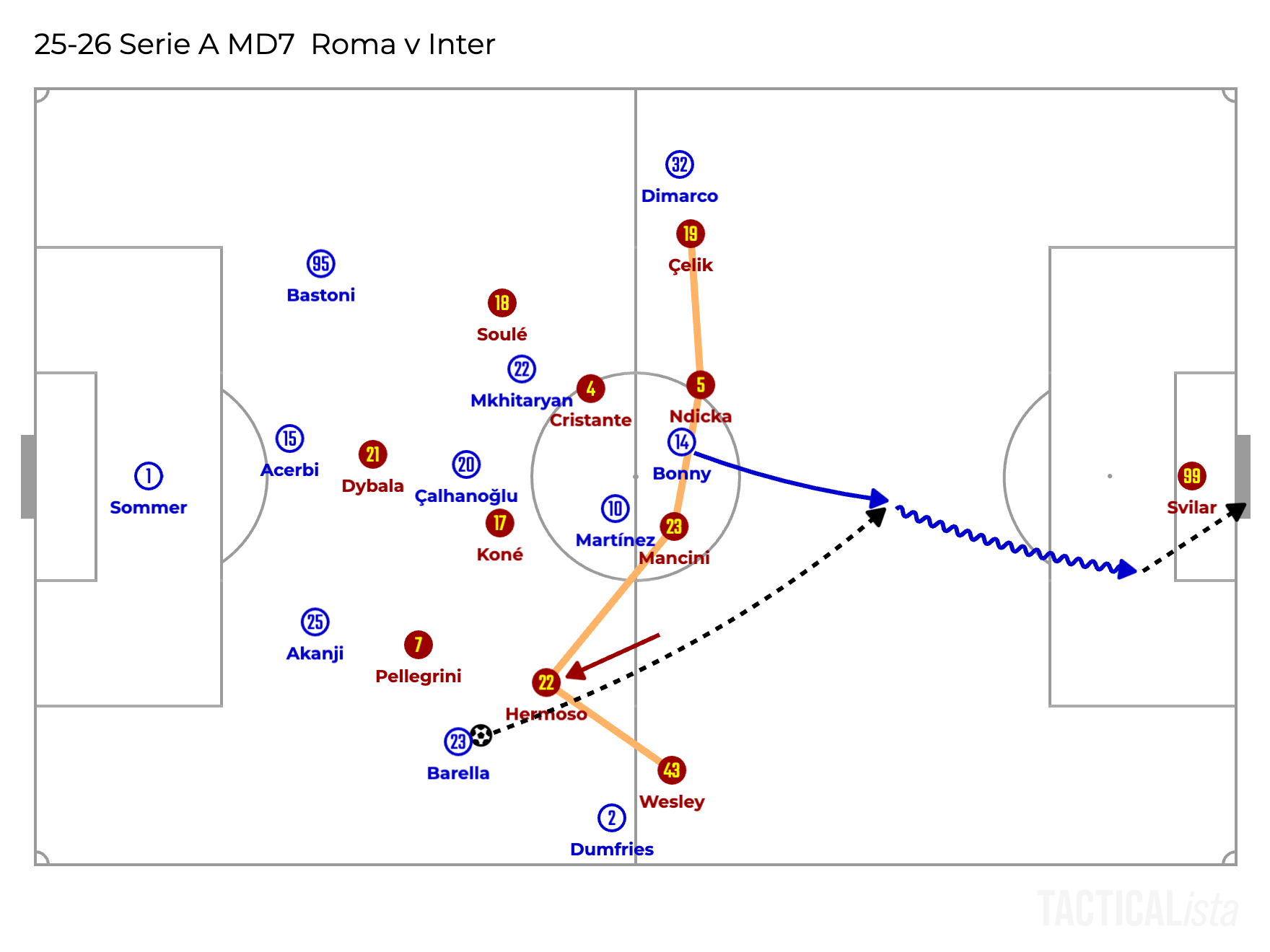

Here is an example of breaking Inter’s defensive block.

The left attacking midfielder Lorenzo Pellegrini drifted outside to be the hub for attacking in the final third like the defensive midfielders did in the build up phase. From him, Roma started to perform the combination.

As Pellegrini left his original position in the left half space, while the ball was travelling down the touchline, the defensive midfielder Manu Koné sneaked into the pocket of space and eventually Paulo Dybala made a run in behind to receive the through ball inside the box.

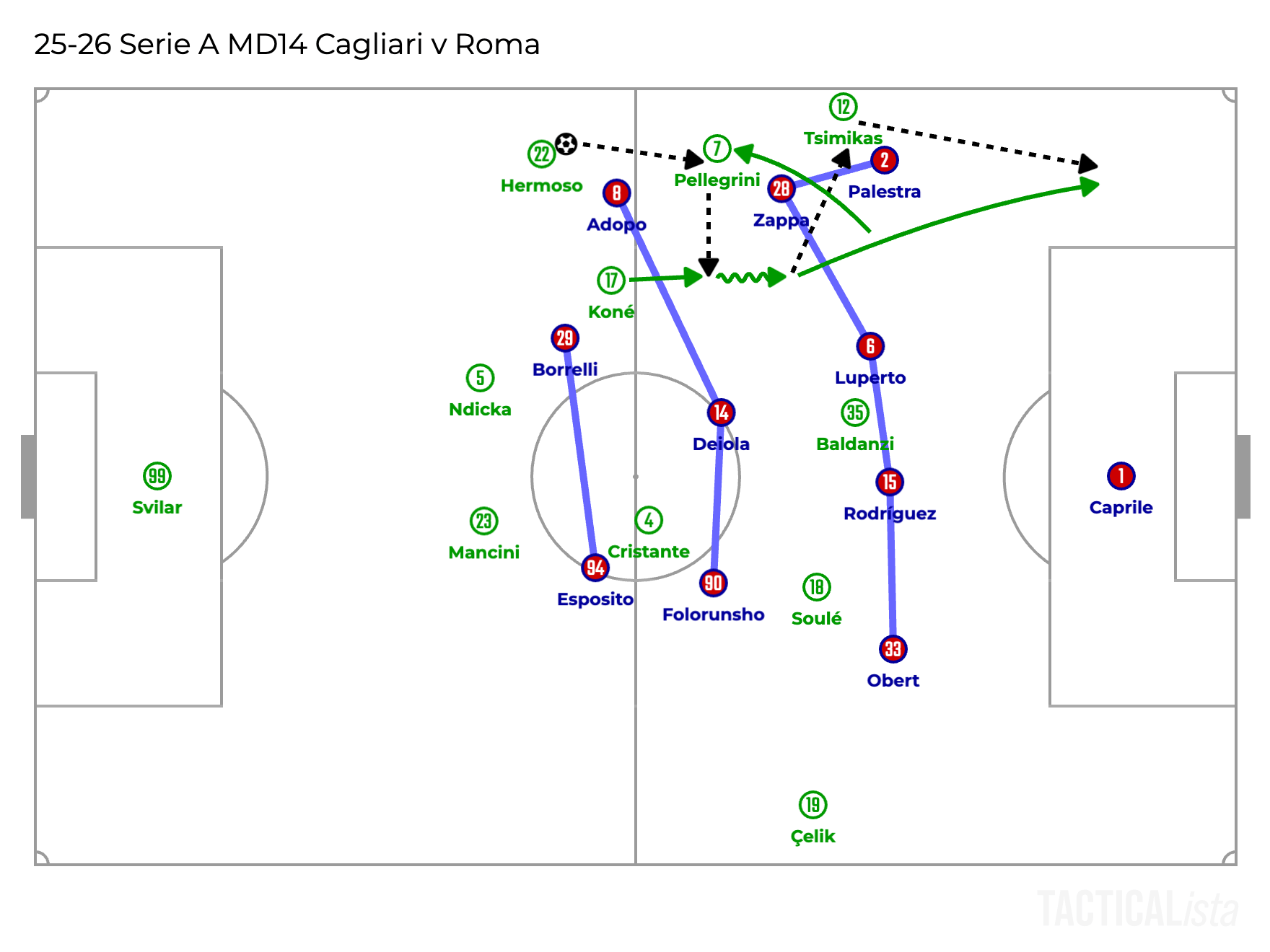

The similar pattern was also found in the game against Cagliari.

Like the combination against Inter, Pellegrini drifted outside and Koné stepped into the space in between the lines, which was vacated by Pellegrini. Then, he played a one-two with Konstantinos Tsimikas to progress down the left flank.

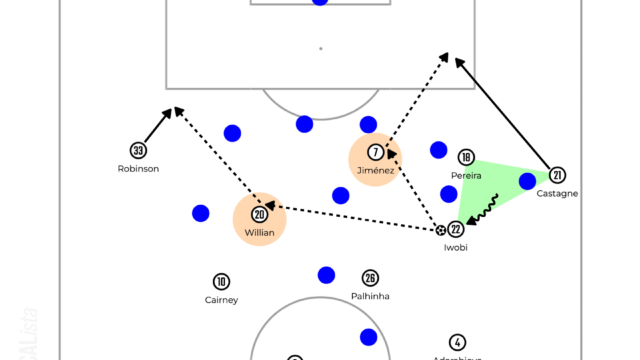

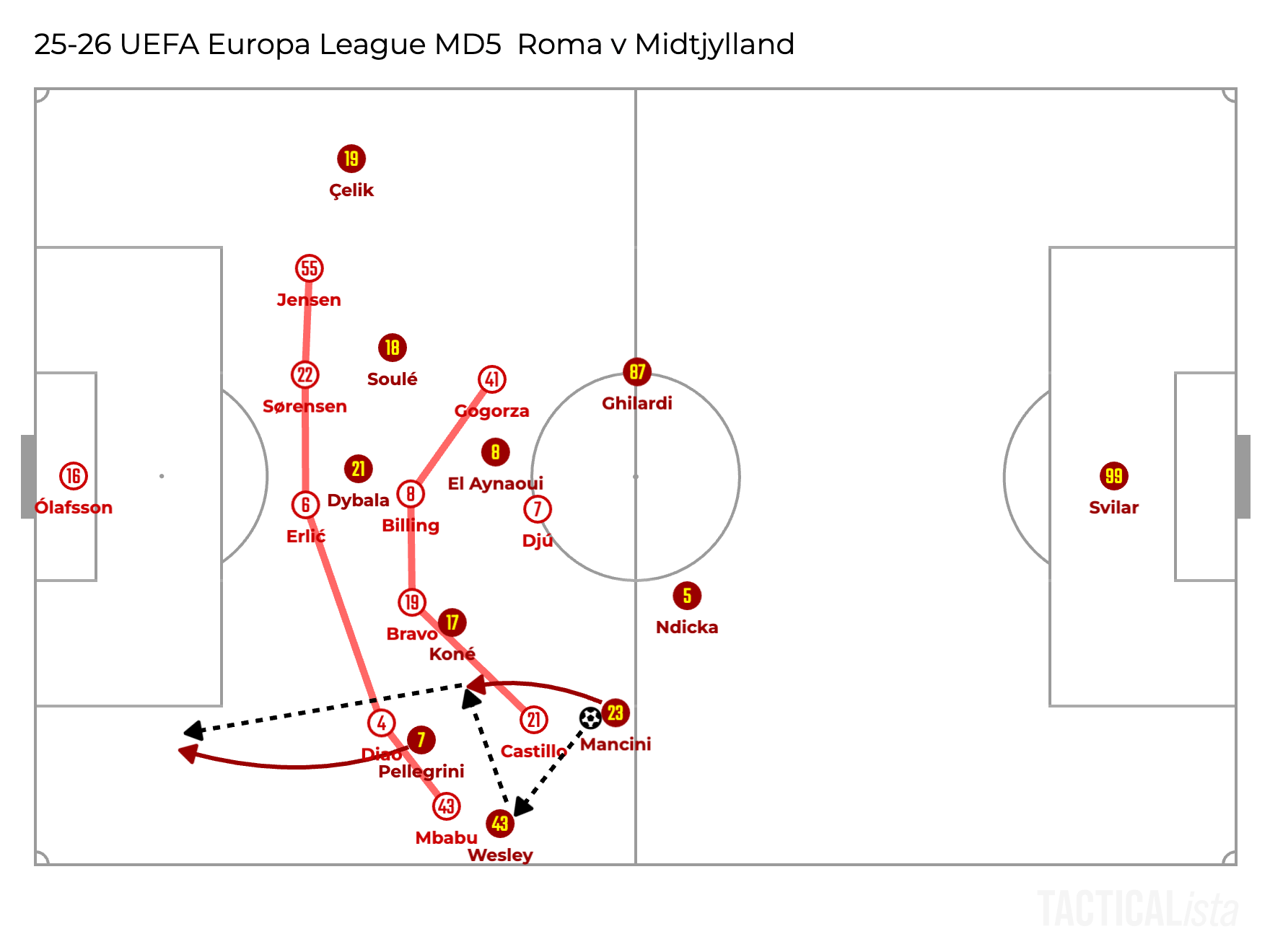

In these two examples, it was Koné to link them up by stepping forward, but it is not the job only for him. The illustration below shows another one.

After Mancini passed the ball to the left wingback Wesley França, he stepped up to play a one-two with him and Pellegrini synced his run to break the opposition last line.

So, like Koné or Mancini, the movement from the back to step forward adds dynamism and increases the tempo or speed of attacks in the wide areas. This is one of the main principles of Roma and Gasperini.

So far, Roma’s attacking tactics mainly from wide areas were discussed, which include the movement of the midfielders to drift outside to create overloads on the flanks. However, by repeating this, the opposition might predict them to only play outside, and this is the moment when Roma can play though the middle.

The illustration below shows that the left attacking midfielder Pellegrini dropped to get the ball and defensive midfielder Koné moved into the space where Pellegrini vacated.

Then, Pellegrini played a split pass into Dybala and he turned forward and accelerated the attack. Finally, the left wingback Wesley made a run in behind and received a through ball from him in the box.

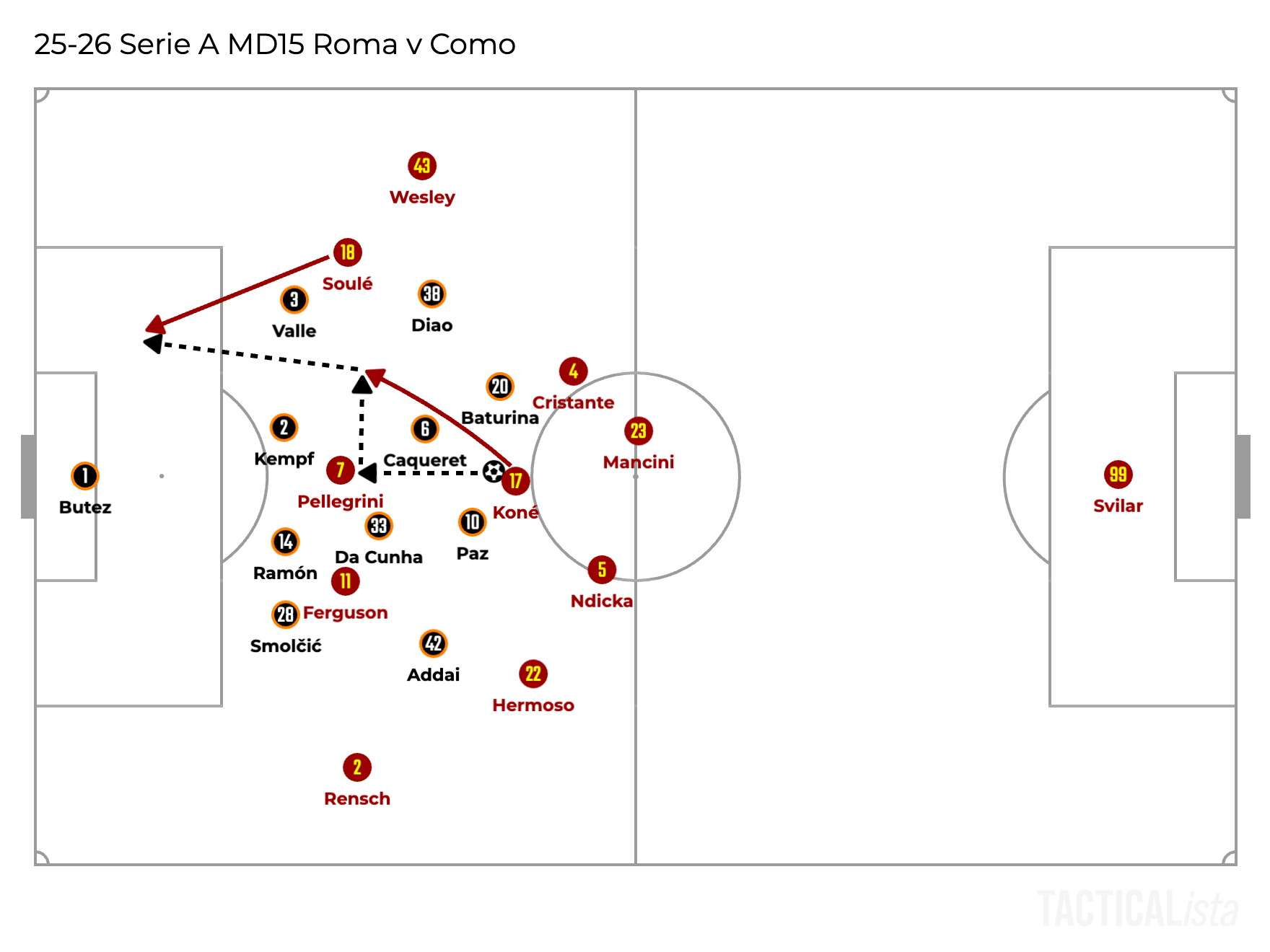

Another method to play through the middle is the combinations from Koné. He is very good at dictating the game in deep midfield and also highly mobile, as it was already mentioned in the previous examples. The illustration below replicates the moment when Roma played through the middle from a one-two with Koné and Pellegrini against Como.

After playing a split pass to Pellegrini, he stepped forward to receive the ball laid off by Pellegrini and played through to Matías Soulé in the box.

What their attacking tactics in wide areas and the middle lane have in common is that the combinations are based on overlapping/underlapping movements after passing the ball. In contrast to the idea of keeping the shape or balance on the pitch, Gasperini encourages the team to be dynamic and fluid, even allowing the defensive midfielders or wide centre backs to attack the opposition box.

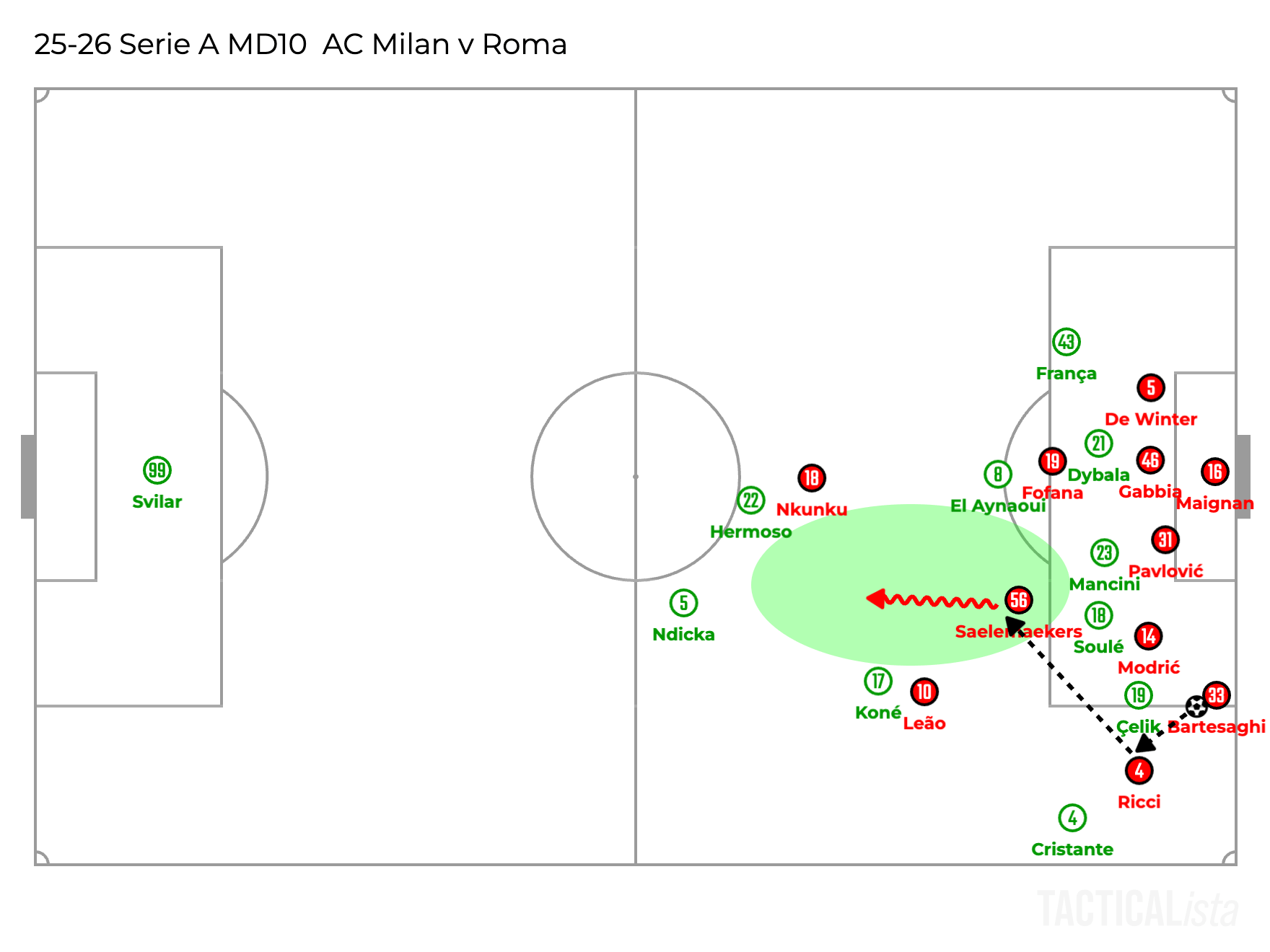

However, whereas this increases the threats in the final third, this also makes their rest defense structure against the opposition counterattacks more vulnerable. Indeed, they conceded a counterattack that gave AC Milan the only and winning goal in the game.

In this scenario, the right centre back Mancini was in the box and one of the defensive midfielders Cristante was positioned higher on the right flank. This forced another defensive midfielder Koné to cover the space left by them and mark Rafael Leão, which vacated the space in the middle.

This is all about the trade-off. By committing more numbers into the opposition box and attacking with greater fluidity, in return, they increase their exposure to counter-attacks. If they became more balanced, they would defend the opposition counterattacks better, but decrease the threats in the box. The last possible way would be just placing better centre backs, and this is also important when they press man-to-man.

Out of Possession

Gasperini had been known to stick to press man-to-man, and at Atalanta, this caused a lot of problems for the invincible side Leverkusen in the final of the Europa League. He hasn’t changed his mind at Roma as well, but probably he needs more time to reach a certain level.

Man-to-Man Pressing

First of all, the ideal pressing outcome will be shared in the illustration below.

Against Celtic, as they tried to play short rather than playing in behind, it allowed the centre backs to easily read the passes to the opposition attackers and step out to intercept them.

This was probably one of the easiest games for them so far, but when the opposition mixed the type of passes to the opposition attackers, it became more difficult for the centre backs to deal with.

The first example of their pressing being beaten was due to the loss of aerial duels.

Cagliari repeated this pattern and the successful one came when Michael Folorunsho flicked the long ball from the goalkeeper. As Roma don’t have an extra defender at the back, each duel becomes more vital. Therefore, if they lose this kind of aerial duels, it allows them to exploit the huge space behind Roma’s last line.

Another example is that even when they could win the first aerial duel, if they couldn’t secure the second ball, the opposition was able to play a fast break.

This time, Ndicka won the first header, but the opposition right wingback Yang Hyun-Jun gained the second ball and they quickly exploited the space in behind.

This can be due to the lack of individual qualities such as power or strength from the centre backs who head the ball back or lack of effort from the other players to drop back to secure the second ball.

In addition to this, the individual qualities matter not only when the opposition plays long but also plays short. When the opposition tries to play out the pressure by short passes, there are a few occasions to close them down. Whether they can win the ball or force mistakes in these situations is extremely important to complete the man-to-man pressing.

On the other hand, however, by trying to close them down but having failed, as they are front-footed, it can be a great opportunity for the opposition to play through the pressing.

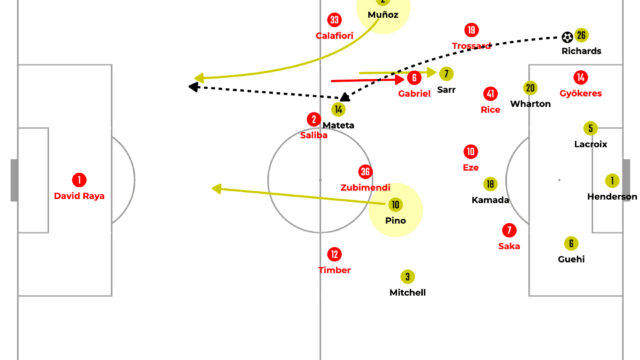

In the illustration above, Napoli successfully played out the pressure with a couple of short passes and switched the play to generate a fast break. Roma successfully locked them in, but they failed to win each duel, resulting in Napoli’s beautiful build up play.

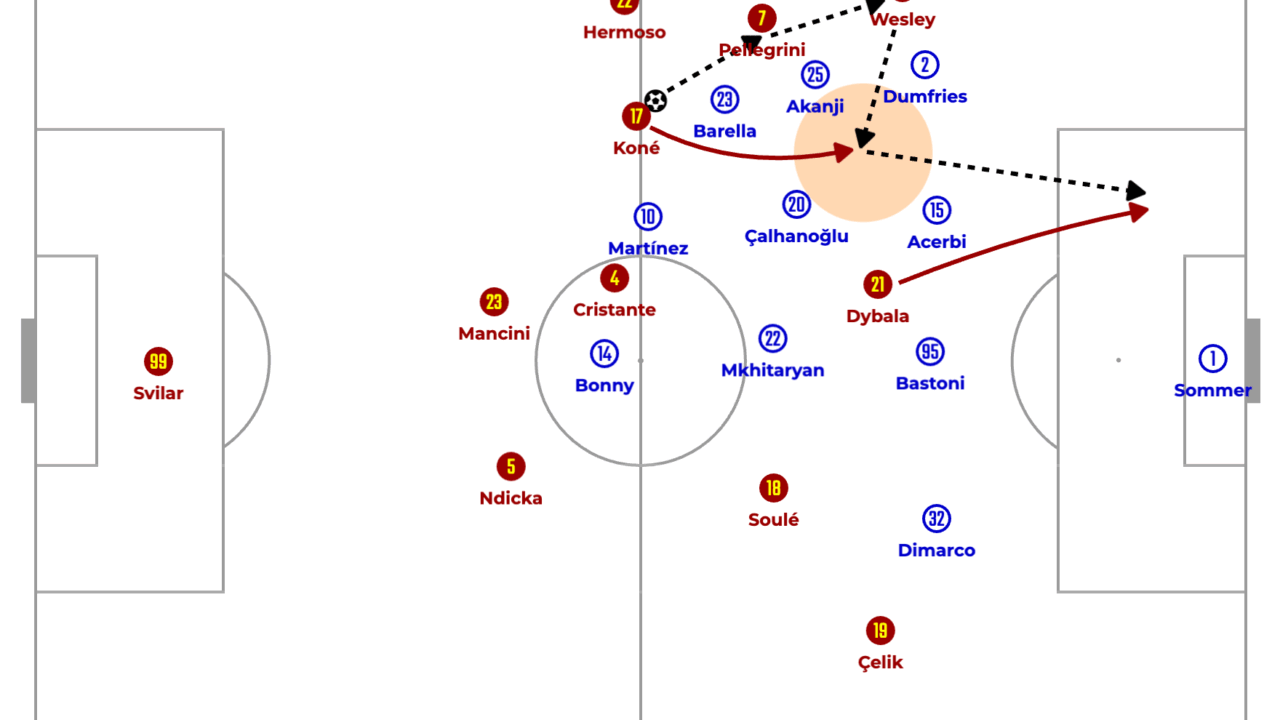

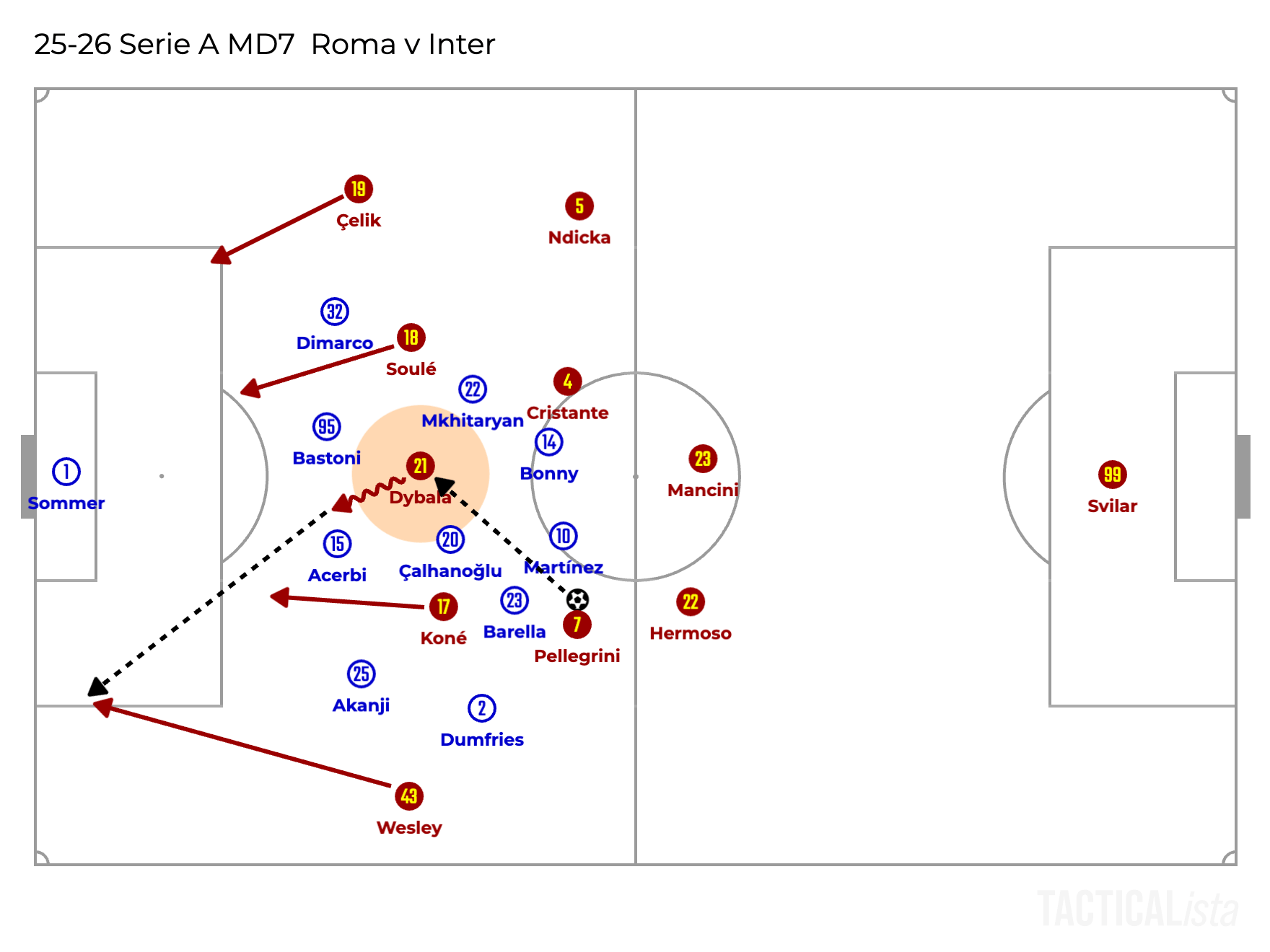

In the midfield, when they are more organised, the structure becomes more important. The illustration below shows how Inter exploited their weakness to get the goal.

Even though when they set the defensive block in the midfield, they are man-oriented, meaning the space isn’t covered well.

Against Roma’s 5-4-1, Inter’s attacking midfielder Nicolò Barella dropped into the space between Pellegrini and Wesley. As Wesley was pinned by Denzel Dumfries, Mario Hermoso needed to step up, leaving space behind him. Mancini was also pinned by Lautaro Martínez, Ange-Yoan Bonny could receive the through ball behind them and beat Mile Svilar in goal.

Overall, in contrast to Roma’s attacking threats, they still need more time to improve in man-to-man pressing. As pressing high with man-to-man approach has been the recent trend, many teams get used to beat man-to-man pressing, so it becomes more and more difficult for Roma. Therefore, Gasperini’s man-to-man is not an exception anymore, and he might need to evolve his trademark man-to-man style. For sure, he has the most experience of this, but adaptation is the key.